Tidy processes often fail. Here’s why…

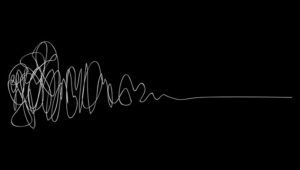

The Process of Design Squiggle (by Damien Newman, thedesignsquiggle.com) is a celebration of the fact creativity is not an ordered and linear process.“The Design Squiggle is a simple illustration of the design process. The journey of researching, uncovering insights, generating creative concepts, iteration of prototypes and eventually concluding in one single designed solution.”

It reminded us of Jeff Conklin’s enjoyable paper about wicked problems and social complexity.

Get ready for some squiggly diagrams, but they point to some reassuringly human ideas.

Conklin uses this diagram of the traditional waterfall process for projects. There are four stages: gather data, analyse data, formulate solution, implement solution:

The waterfall model

But is this how real projects actually unfold? Researchers looked at how successful designers (of an elevator control system) operated. They plotted how one of the designers actually spent their time against the waterfall:

One designer’s workflow plotted…

It’s clear they don’t follow the waterfall at all. Instead they jump from one area to another. They might think about where to put the lift buttons (implementation), and then that might make them think about the average height of users (data). And so on. That’s how our minds actually work.

The researchers then looked at a second designer on the team, plotting them on the same chart:

Two designers plotted…

This designer has a different focus from the ideal and from their colleague.

In the real world, creative people don’t follow the idealised script.

We often hear that meetings fail because people “don’t stick to the agenda.” But we believe the reverse can also be true. For complex challenges, people need to wander more freely as they reflect on many different aspects of the problem. If we force them to only generate ideas in the morning, and only focus on practical action in the afternoon, we’re probably interfering with their ability to think intelligently.

Good facilitation is often about embracing the spikes, not flattening them. We need to make it easy and acceptable for people to branch off rather than forcing everyone into a plenary vortex where they have to pretend to go one step at a time. For instance, Open Space allows much more fluid, wide ranging conversation. Unhurried Conversations also support more diverse, eclectic ways to explore ideas. Jim Rough’s dynamic facilitation also responds to this challenge.

(Photo by Alex Siale on Unsplash)